Diversity in the outdoors

We're exploring our diversity at Outward Bound: taking the first steps in creating an instructional team that more closely represents the backgrounds of the young people we work with. In this blog, project manager Kate shares her findings to date.

Over the last nine months I have consulted internally across The Trust, and externally amongst national governing bodies, higher education and other employers as well as engaging with research from within the corporate, public, charity and education sectors. What has become clear is that this is definitely not about creating divisions between groups of people, but enhancing understanding among individuals who all have different lived experience of the world. There are some obvious under-representations in our workforce at Outward Bound and in the outdoor sector more broadly, which if understood and considered may offer further benefit and impact to the many young people from diverse backgrounds who experience our programmes.

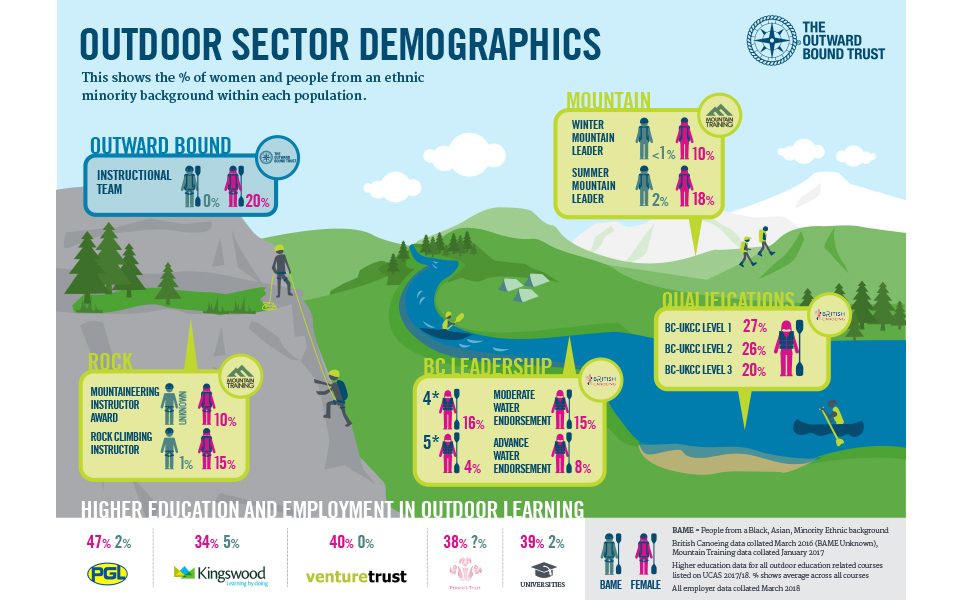

We have collected information available regarding the current make up of relevant parts of the outdoor sector.

People from an ethnic minority background in the outdoors

In many ways grouping together “people from an ethnic minority background” into an under-represented group in the outdoors offers a challenging start point in itself. Because of course within this grouping there is a huge diversity of traditions, religious beliefs, language, not to mention gender, social class and education. People may be first, second, third (or more) generations new to this country. Depending on where they live they may be in a minority or majority within their immediate community settings. These multiple factors play a huge part in people’s participation and engagement with society more broadly, but also with the outdoors. Studies show that often members of a dominant group (in-group) tend to see individual differences within their group, however often will clump together members of minority groups (out-group), viewing them as all very similar, which leaves thinking vulnerable to stereotyping and generalisation .

Around 14% of the population of England and Wales are from black, Asian, minority ethnic backgrounds, in Scotland this is 4%. The figure is higher for the under 16 population, and is increasing steadily. The most ethnically diverse place is London, and we know that the majority of people from an ethnic minority background in the UK live in urban areas. Approximately 15% of young people who visit Outward Bound centres come from an ethnic minority background.

Research shows that the majority group who participate in the types of outdoor activities which contribute to developing the skills and motivation required to work in outdoor education are white, male, middle class and living in affluent areas. People from an ethnic minority background visit outdoor spaces less, and when they do it tends to be within 1–2 miles from home, taking part in more urban outdoor activity such as park visits and street sports.

UNDER-REPRESENTATION IN THE OUTDOORS IS LARGELY LINKED TO PEOPLE’S EXPERIENCES IN THE UK, RATHER THAN NEGATIVE ATTITUDES LINKED TO ETHNICITY, CULTURE OR RELIGION.

Recent Sport England research identifies the six themes of language, awareness, safety, culture, confidence and perception of middle class stigma as barriers to participation in outdoor activities for people from an ethnic minority background. A diversity review commissioned by DEFRA goes into more depth highlighting several key factors in understanding these lower levels of participation. One of the key findings from this report is that although the people interviewed valued the natural environment, they often had negative perceptions of the social environment, expecting to feel excluded and conspicuous in what they perceived to be an exclusively English place. The report goes on to highlight that under-representation is largely linked to people’s experiences in the UK, rather than negative attitudes linked to ethnicity, culture or religion. A sense of acceptance (or non-acceptance) in wider society can have a disproportionate affect on people from an ethnic minority background’s leisure time. When people feel that they cannot engage with the mainstream culture as their authentic selves they tend to limit contact with dominant groups and places where feeling like an outsider is amplified, and may raise concerns around safety. Some cultural differences in perception of outdoor activities were also identified, for example some participants identified activities such as walking with hardship and a lack of wealth, having to walk being an enforced necessity due to not being able to afford a car, rather than a pleasurable leisure choice. Practical concerns were also identified such as travel distances to wild places, sleeping and eating provisions to cater for different cultural preferences.

Women in the Outdoors

UK society is 51% female. Yet we know that there are less women and girls participating in the types of outdoor activities likely to lead to the interest, skill and motivation to pursue a career in this area. Recent research shows that 13–15 year old girls are the least active population in the UK. This lower representation persists into adulthood and into the qualification pathways for outdoor careers.

It is worth digging a bit deeper if we are to make progress and act in a way which contributes to genuine change which will benefit future generations of young people. There were five themes which stood out as being reflected in the extensive body of academic research in this area, as well as highlighted by current Outward Bound employees throughout this piece of work.

1. Males and females are treated differently

From the moment a child is born he or she is treated differently dependent upon biological sex. The recent BBC documentary, No More Boys and Girls: Can Our Kids Go Gender Free?, highlights much of this gendered socialisation process and the powerful impact it has within society. Within the outdoor sector, research carried out by Sport England shows that in 2018 young girls still consider that they are not welcome in outdoor play spaces and families have concerns particularly in allowing their daughters to play and explore outside.

By the time young people come to make choices about how they want to spend their leisure time, what types of behaviours feel safe, or what career path to choose, they have already experienced a lifetime of messages and conditioning creating a different start point for young men and young women. Many women carry the baggage of living in a society which is structured by a series of binary oppositions in which one side can be feminised and associated with an inferior realm of life. Consider sayings such as "crying like a girl" or "man up", which are still heard. Language can often appear trivial with the impact being invisible to people who live on the side of life which benefits from being deemed superior. Or perhaps the impact is different, a need to appear strong, not show weakness through emotional vulnerability. Society’s ideas about masculinity and femininity have implications for both genders in developing the ability to become well rounded outdoor professionals capable of leading authentic adventures and facilitating quality personal development.

2. Values and motivation

Within outdoor education it has been shown that there is a valuing of physical and technical skills over interpersonal skills. But intriguingly women are expected to use interpersonal skills more than men, and men expected to use more physical skills. Multiple studies over the past 30 years also show that men and women have some differing motivations in pursuing a career in outdoor education, recent internal research mirrors this. Female staff at Outward Bound are three times more likely to cite personal development through the outdoors as a primary motivator for working in the sector, while male staff are more likely to cite the high level of adventure or expeditions as a primary motivator. This is not to say that male staff don’t value or aren’t motivated by personal development or that female staff don’t value or aren’t motivated by adventure. But what it does suggest is that if you have a room full of male staff, it will be more likely that more of those people will be intrinsically motivated by the adventure elements of the role and if you have a room of female staff it is more likely that more of those people will be intrinsically motivated by the personal development aspects of the role. Valuing physicality and technical competence more highly within the leadership, structures and subculture of many outdoor education settings is more likely to be congruent with male values and motivations. This may impact on some women’s experiences of the working environment and how they feel able to contribute and progress within it.

3. Measuring up – in whose world?

Historically outdoor education has focused on traditional masculinised physicality to represent competency. The perception that the outdoors and adventure require qualities associated with being a particular type of male (including traits such as strength, toughness and physical mastery) has meant that many women (and likely men who fall outside of this type) have struggled to find validity in their experiences. Spending lots of time in male dominated environments, can lead some women to ask unhelpful questions of themselves - “how can I be good enough?”, rather than, “how can I learn to do this in a way which is appropriate for me, and successfully achieves the objective?” This questioning of competence can lead to a longer journey for people who don’t fit in with the traditionally masculinised notion of adventure and leadership, with women often taking 10 years longer than men to realise how good they actually are.

4. Women are inadvertently complicit in the gender imbalance

One of the interesting areas which stood out from the research is perhaps slightly counter-intuitive but an incredibly important piece of the gender asymmetry puzzle, is that women often hold themselves back from opportunity or progression. This can be subtle, by wanting to distribute credit or nurture others sense of self efficacy, rather than shout about achievements. But also, in not wanting to step forward for leadership roles, technical assessments or roles requiring the limelight eg publication or promotion.

5. Practicalities

For many women having a family is a strong driver. It has long been known that a career in the outdoors is not particularly compatible with being a primary care giver and this is a significant factor in women choosing to leave. Many women spoke of the difficulties they faced with this, how dedicated they were to their career and professional development, but that family would come first.

All of the above factors (as well as others) can be inextricably linked together contributing to the picture we see representing training, progression and employment within the outdoor sector.

Does it matter?

OK, so we know that there are less women and people from ethnic minority backgrounds in the outdoor sector… but why does that matter? Some will argue that it doesn’t matter who is leading the adventure as long as they are a good instructor. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that role models do make a difference to how young people view themselves and their sense of what is possible in their own future. Many outdoor organisations, like The Outward Bound Trust, exist to have a positive impact on the development of individuals lives. Research within the social sector makes the pertinent point that:

A charity is not there to serve its own purposes but to help drive social change and positive impact. That task is harder if the organisation itself is exclusive.

There is also growing evidence to support the impact that bias (conscious or unconscious) can have on leadership. Despite best intentions and a belief in equality in its broadest sense, people can, and do, sometimes respond unhelpfully to others who are different. Or act unconsciously in a way which perpetuates the status quo and unintentionally benefits some, and not others. This becomes more likely when we surround ourselves by people who are similar to us, in friendships… communities… workplaces. This becomes our world, our normal. We exist in a bubble and perhaps find it hard to imagine that things could be different. Better, for everybody.

Changing World

There are some fantastic initiatives happening within our sector already. The RYA are investing in developing sailing initiatives to engage more people from an urban and ethnic minority background. Lindley Educational Trust and Shadwell Basin Outdoor Centre are both doing fantastic, progressive work in diverse urban communities. Mountain Training have devoted significant time to considering how their training structures can attract and support candidates from different backgrounds. The National Training centre, Glenmore Lodge, now offer female specific programmes and also hold the annual Women In Adventure conference. Online there are numerous popular and successful sources of female inspiration and groups offering support and a different way of being in the outdoors.

Now we have a better understanding of our start point, both within Outward Bound and within some of the key parts of the sector, we will begin to take some actions. We hope that we can learn from, build on and create strong partnerships with some of the above examples, as we embark on taking the first steps to attracting and retaining a workforce which is more representative of the backgrounds of the young people we work with.

If you are interested to find out more please email Kate.

Further Reading

Exploring our Diversity

22 January 18

Creating a diverse team.

A collaborative approach to diversity

16 July 20

The latest on our work to increase diversity and equity in the outdoors.

Travelling to equality

14 November 19

The journey to a Women's Outdoor Leadership Course